https://www.haytap.org/tr/haytapfighting-for-long-term-change-for-animals-in-turkey?fbclid=IwY2xjawEYXntleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHaLlVyeNpbYCbL3st5j3NyV3kNWRa_OBfBaHf7CUn3rzT2Lmn2niphAYGA_aem_hq7RtpZmZSkn7J3WGvDM5A

Haytap—Fighting for long-term change for animals in Turkey

Before Haytap, the first Turkish animal rights federation, numerous isolated associations had been struggling for years, focusing exclusively on rescuing local stray dogs and cats. Those kind individuals were so exhausted and resource-strapped that they couldn’t catch their breaths and plan far ahead. It took Ahmet Kemal Şenpolat, a lawyer with a broad perspective, long-term commitment and strategic thinking to create a national umbrella federation with national influence and a clear agenda. But change, no matter how needed, can be painful and face opposition. In this case, Şenpolat’s inclination to spend money on countrywide awareness campaigns was sometimes a tough sell to local rescuers who care for hundreds of dogs and can’t always afford to feed them. This is the story of how an important change of focus took place in the Turkish animal advocacy world.

Before Haytap, the first Turkish animal rights federation, numerous isolated associations had been struggling for years, focusing exclusively on rescuing local stray dogs and cats. Those kind individuals were so exhausted and resource-strapped that they couldn’t catch their breaths and plan far ahead. It took Ahmet Kemal Şenpolat, a lawyer with a broad perspective, long-term commitment and strategic thinking to create a national umbrella federation with national influence and a clear agenda. But change, no matter how needed, can be painful and face opposition. In this case, Şenpolat’s inclination to spend money on countrywide awareness campaigns was sometimes a tough sell to local rescuers who care for hundreds of dogs and can’t always afford to feed them. This is the story of how an important change of focus took place in the Turkish animal advocacy world.

Turkey’s huge stray problemAlthough there are no official tallies, the stray dog population in Turkey is roughly estimated at between 100,000 and 150,000. Such large numbers are explained by several factors.

For one thing, it’s legal to breed and sell animals in Turkey, so lots of people get into the business, opening pet shops in shopping malls. For another, hundreds of purebred puppies and kittens are illegally brought in, smuggled inside travelers’ luggage. There’s also the myth, perpetuated by uninformed local vets, that “breeding is good for the animal’s health.” With so much importing and breeding and so little spaying and neutering, populations increase rapidly and large numbers of pets and/or their litters are abandoned on the streets every day.

The country has long struggled over what to do about this problem. While killing pets openly has always been illegal in Turkey, strays have an ambiguous status and little protection. The weak laws that do exist are poorly enforced. In fact, the government has often moved against the

strays. In 1910, thousands of dogs were deported to an island off Istanbul, where they were left to starve. As recently as 2012, the Environment and Forestry Ministry proposed to round strays up again and put them in “wild life parks.” Fearing that the scheme would lead to virtually the same result as in 1910, thousands of Turks in cities across the country took to the streets in protest, and the national government backed down. Even so, on a regular basis, some municipalities still collect strays and abandon them in deserted forests.

Individual acts of kindnessTo try to remedy the problem in kinder ways, good souls all over Turkey rescued and fed as many local strays as they could. Armed with the best intentions but with insufficient resources, small animal rights associations and individual activists tried to foster animals until they could rehome them. Too often the result was that foster homes had to adopt the poor things themselves because nobody else would. With more animals than they could personally care for, most rescuers would then have to stop their fostering work. As a result of this inefficient cycle, only a very small percentage of animals in need were saved, and those lucky few were almost exclusively cats and dogs. There was no ability to try to improve the lives of farm, work and show animals.

Melding individual actions into a national force—the founding of HAYTAPOne person in the animal rights movement stood apart and became known for his broad vision and long-term goals. Ahmet Kemal Şenpolat is a lawyer who realized that solving animal problems in Turkey required macro-level solutions that only an NGO could champion. Only a national association, he believed, would have the stature, draw the media attention and exert sufficient influence to affect policy making and the promotion and implementation of pro-animal laws.

.jpg) Şenpolat began reaching out to disparate Turkish animal rights associations with the message that “union makes strength.” He explained that if all the small organizations came together under one roof, they’d have political power municipalities and policymakers wouldn’t be able to ignore. He also said that while showing kindness to the stray dog in front of your house is admirable, it’s not a long-term solution. Significant changes would be needed to save hundreds of thousands of animals.

Şenpolat began reaching out to disparate Turkish animal rights associations with the message that “union makes strength.” He explained that if all the small organizations came together under one roof, they’d have political power municipalities and policymakers wouldn’t be able to ignore. He also said that while showing kindness to the stray dog in front of your house is admirable, it’s not a long-term solution. Significant changes would be needed to save hundreds of thousands of animals.

Here’s an excerpt from one of Senpolat’s numerous articles:

“Unless we are strong, the disproportionate forces of government institutions—particularly municipalities—will be rolling over our abandoned friends like panzers. They don’t think twice before using their power whenever they can. So far, this is the main reason for our inability to prevent the poisoning, killing and dumping of animals in the woods. The responsibility is not theirs entirely, but ours as well, since, until now, we’ve been unable to organize and institutionalize… It’s clear there is no need to reinvent the wheel. We can’t go one step further without strong NGOs.”

Not everyone agreed. In fact, Senpolat’s position set off a real grassroots struggle among activists. There was a lot of opposition from some of the animal rights associations to the idea of spending resources on awareness campaigns. For rescue organizations trying to care for a couple of hundreds of dogs, it wasn’t easy to think about sacrificing present needs to achieve the long-term goals Senpolat was proposing. Dogs don’t eat leaflets or brochures, some activists objected, so any funds raised for animals should go to buying food for them.

Personally, I get where they were coming from. I met Senpolat in 2006 at an animal rights event. Being a strong rationalist, I knew he was correct, but still I kept rescuing and rehoming for a few more years after we met. You keep running into a dog or a cat on your way to, say, work, and you know this is an animal who clearly will not be able to survive in the streets if not taken in by somebody.

Fortunately, the majority of animal rights activists in Turkey have gradually adopted a broader vision. HAYTAP, the first animal rights federation of Turkey, was founded in 2008. Today subscribers to its monthly newsletter number more than 30,000. What’s more, Haytap is strong and sufficiently funded to support many animal shelters and rescue campaigns while also continuing to work toward its long-term goals of national attitudes, practices and laws.

Changing the conversation

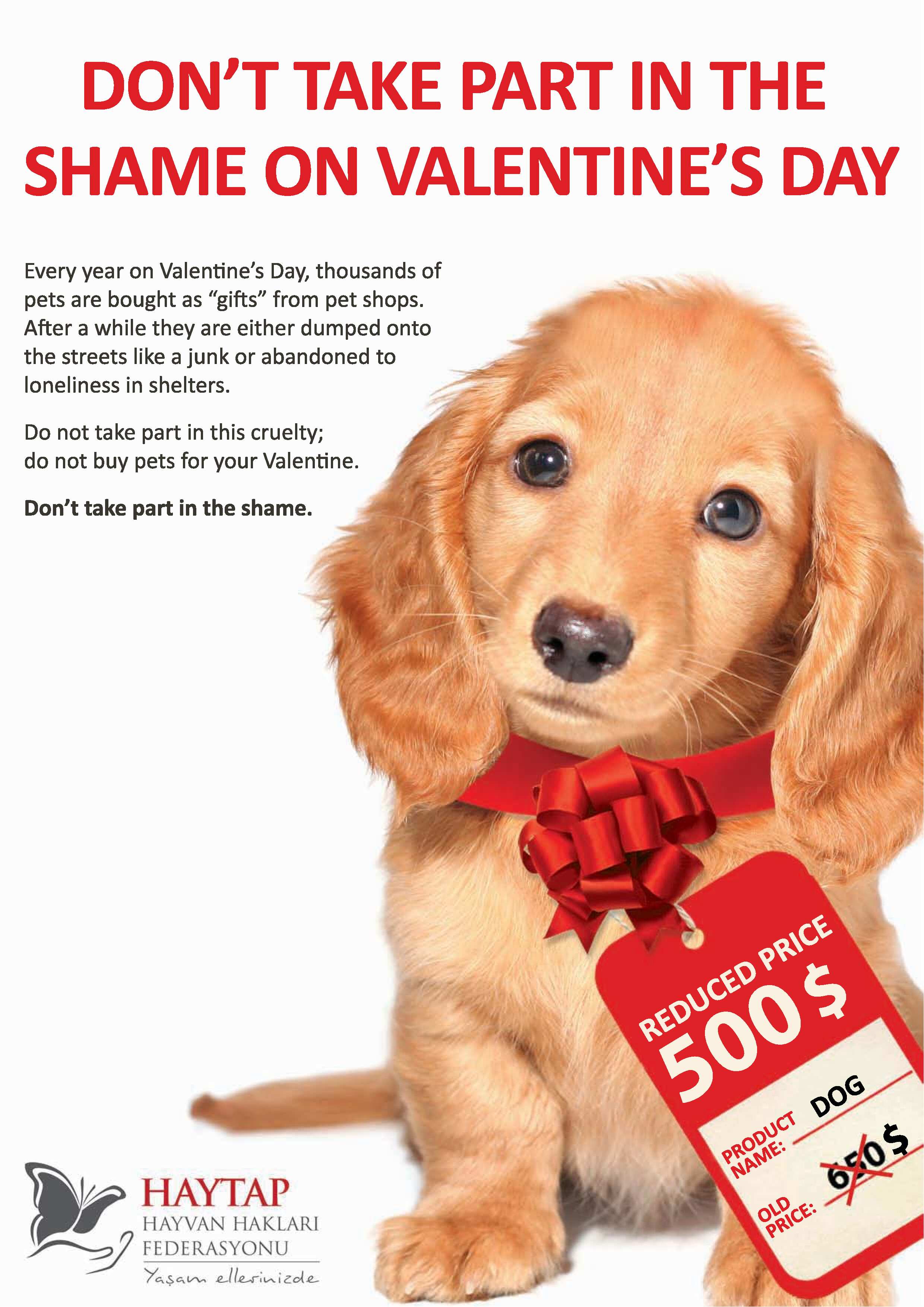

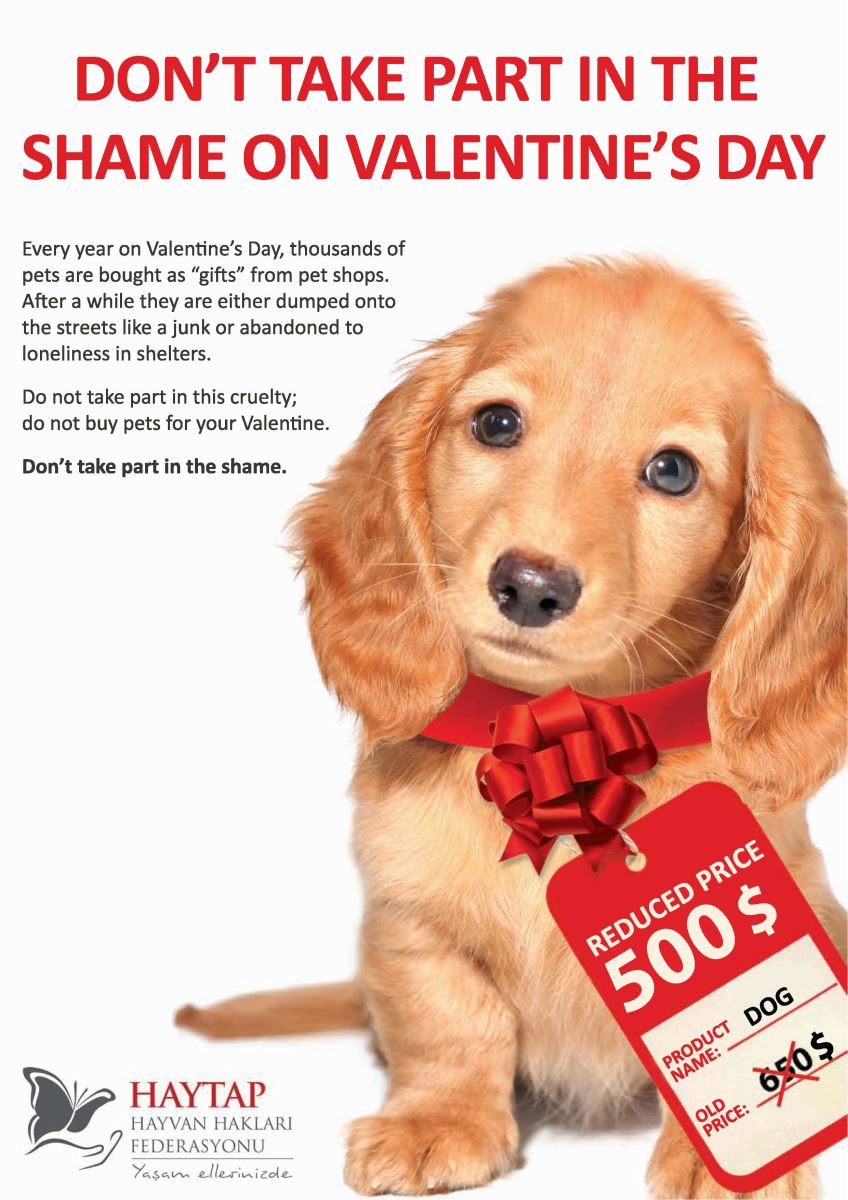

One of Haytap’s most important accomplishments is changing the conversation about animals in Turkey. The association’s numerous awareness campaigns have made an impact.

For instance, in the past, animal-related events and meetings would usually focus on the “stray animal problem,” which refers to the complaints of people about stray animals in their neighborhood.

Haytap attended those events and started talking instead about “the problems of the stray animals.” They got people to think instead about the problems animals are facing because of people who breed, import, or buy and abandon them, and because of municipalities that fail to spay/neuter and vaccinate. They shined a light on insufficient laws that allow all kinds of animal trade. They shifted the discussion from “how to protect humans from stray animals” to “how to protect the stray animals and control their population.”

And to encourage empathy and soothe the fear some Turks have of stray dogs, since they’re so numerous and often walk in packs, Haytap has made movies like this one.

Haytap has also broadened the conversation to include not only cats and dogs, but all animals. Breaking from the activism from past, the federation’s campaigns are also raising awareness of the need to fight against animal abuse in dolphin parks, horse carts, circuses, zoos and farms.

Haytap has also broadened the conversation to include not only cats and dogs, but all animals. Breaking from the activism from past, the federation’s campaigns are also raising awareness of the need to fight against animal abuse in dolphin parks, horse carts, circuses, zoos and farms.

Getting the ear of governmentHaytap is bringing the new broader conversation to national and municipal governments as well—a first step toward its ultimate goal of changing the laws to support animals. A Haytap-led group met with Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan to urge stronger punishments for animal abusers and the elimination of the current practice of letting the convicted avoid punishment by paying an administrative fee. Istanbul Mayor Kadir Topbas also took a meeting with Senpolat, who was accompanied by other well-known individuals from across Turkish society, including pop singers Yonca Evcimik, Ajda Pekkan, Metin Özülkü and Burcu Güneş, journalist Ömür Gedik and actress Tuna Arman. Beyond these specific, high-profile meetings, Haytap is constantly involved in urging authorities at the national and municipal levels to eliminate pet importation and implement effective spaying/neutering events.

The largest animal rights resource in Turkish

The NGO’s website is an immense resource for Turkish-language people concerned with animal rights. It’s a place to find out about Senpolat’s book, “Animal Rights in 111 Questions,” and to read numerous informative articles on a wide range of topics, including circuses, pet shops, the fur industry, animal experimentation, hunting, draught animals (used to draw a load, like a cart), dolphin parks, animal fights and farmed animals —including some in English versions.

To support HaytapUsers of www.sosrooms.com can support Haytap for free. Just go to this affiliated ( booking.com ) site (English, German and Turkish), Booking.com pays a small commission to Haytap at no extra cost to you.

Check out Haytap’s Facebook English page and Instagram account for recent and updated works of Haytap .

To make a donation directly to Haytap, here is their banking info

More :

https://www.haytap.org/tr/haytapfighting-for-long-term-change-for-animals-in-turkey